Back to How Tests Evolved

Back to How Tests EvolvedArt As A Tool For

Adjustment

Copyright 1978/1986/1989 by Rawley Silver, reprinted with permission

from its original publication.

No portion of this work may be copied without written consent by Rawley Silver.

The following are excerpts from

Silver, R. A. (1989). Developing cognitive and creative skills through art. New York: Ablin Press.

Drawing and painting, like dreams and daydreams, can tap the unconscious-condensing, symbolizing, and expressing experiences. Language is the usual medium of psychotherapy, and talk about drawings is the usual medium of art therapy, but art experience can be healing in itself without talk, if need be, by fulfilling wishes vicariously, ventilating feelings, reducing isolation, and providing opportunities to cope with problems and to adjust to disappointments.

page 29.

One way that art experience can be therapeutic is through fantasized gratification. Daydreams or dreams that represent wishes as fulfilled actually do provide partial gratification, according to the psychiatrist Charles Brenner. A thirsty dreamer, dreaming of quenching his thirst, goes on sleeping (Brenner, 1974, p. 66).

Some children seem to use their drawings to obtain in imagination what they cannot obtain in real life. The drawings made by Kenneth (Figures 26 and 27) seem to have served this purpose. Kenneth, age fourteen, was conspicuously small for his age, but once, when angry, he picked up and threw a school desk. He had receptive and expressive language impairment, bilateral hearing loss, and motor handicaps suggesting cerebral palsy. In his drawings, motorcycles, flags, and military uniforms were recurrent themes. In Figure 26 he has a glamorous companion. In Figure 27 he rides alone. His drawings seem to have served the function of giving him, vicariously, power and strength.

Figure 26. Kenneth and friend on motorcycle

To the extent that art experiences can enable a child to identify with heroes, it can diminish the energy of repressed wishes, enhance ego strength, and provide gratification.

page 29.

Children try to experience a broad range of events vicariously. The usual procedure, according to Bruner, is to substitute words and sentences in place of events in order to have a trial run on reality (Bruner 1966a, p. 58).

Language-impaired children sometimes use drawings in place of words to have trial runs of their own. The scene in the graveyard, mourning the death of a dog (Figure 28), was made by the child who dictated his fantasy about killing the bees (Figure 11).

(Picture found in, Silver, R. A. (1989). Developing cognitive and creative skills through art. New York: Ablin Press.)

The girl who had more than $90,000 (Figure 14) also had fantasies about romance. In her first drawing, the boy rescues the girl in the water, while back on the beach, unaware, others are having a picnic (Figure 29).

(Picture found in, Silver, R. A. (1989). Developing cognitive and creative skills through art. New York: Ablin Press.)

In the girl's next drawing, the boy and girl sail away under a cloudless sky. John declares his love and Jackie replies, "Oh thank you" (Figure 30).

Figure 27. Kenneth and motorcycle, #2

(Picture found in, Silver, R. A. (1989). Developing cognitive and creative skills through art. New York: Ablin Press.)

Figure 28. Mourning the death of a dog.

page 29-31.

EXPRESSING

UNACCEPTABLE FEELINGS IN AN

ACCEPTABLE WAY

According to Brenner, repressing unwanted thoughts and feelings makes them unconscious, and each repression diminishes ego strength, since it requires an expenditure of energy to maintain the repression and to keep thoughts under control (Brenner, 1974, p. 81). To the extent that art experience can help children project anger or fear indirectly through symbols, it can help them express unwanted feelings. Symbols do not state directly, as Jung observed. They well up from the unconscious and are vague, unknown, never fully explained. Signs are linked to conscious thought and simply denote the objects to which they are assigned. Symbols express indirectly by means of metaphor (Jung, 1974, p. 43).

Drawings can enable a child to release energy indirectly rather than repress unwanted feelings or act them out. In Figure 31, Michael, age eleven, used the metaphor of slaying a dragon.

In Figure 32 a murder is taking place. The victim is being shot and thrown overboard at the same time, while from above him on the ship a cannonball is aimed at the man who shoots.

Figure 31. Slaying a dragon

In Figure 33, done by a fourteen-year-old, sticks of dynamite are tied to a tough sergeant, and the fuse is lit. One little soldier salutes the sergeant.

(Picture found in, Silver, R. A. (1989). Developing cognitive and creative skills through art. New York: Ablin Press.)

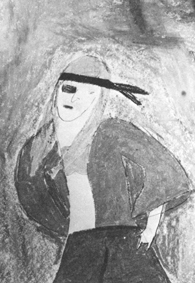

In Figure 34, Michael, age eleven, seems to have symbolized anger itself. He was always cheerful in the art class, and I had no idea of his behavior elsewhere until I read school records that described him hitting children without apparent provocation, being rude to adults indiscriminately, and recently sticking the point of a pencil into his finger.

Figure 34. Michael's angry man

Some children depicted scenes of violence almost as soon as they realized they could draw what they wished. Mark liked to paint traffic accidents (Figures 35 and 36).

page 33-35.

Children who have difficulty verbalizing anger have difficulty ventilating frustrations, and, without some expression, anger can turn into rage. Like the tragic dramas of ancient Greece, drawing and painting can serve as catharsis, restoring inner harmony and balance.

Some children in the experimental classes followed up angry drawings with drawings that seemed to reverse the action. In Figure 37, for example, Larry made a pencil drawing of a man and woman, then painted wounds on their faces, and finally painted stitches on their wounds. If he had repressed his anger at the people he represented, he might have turned it upon himself. If he had expressed his anger directly, he might have been punished. The fact that he undid the damage suggests that his anger had been spent, at least for a while.

Figure 38. "The lady got a pencil in her eye . . ."

Otto explained his drawing (Figure 38) as follows: "The lady got a pencil in her eye. It is covered with tape. The man is a priest. He was smoking a cigarette which got smashed." Making this picture apparently provided some relief: immediately afterward he depicted a smiling astronaut climbing out of a spaceship following a splashdown (Figure 39).

Figure 39. Splashdown of a smiling astronaut.

Giving form to feelings does not necessarily relieve tension. Underlying problems remain. Using the same symbols repeatedly may indicate that the problems are deep-seated and unresolved. Otto drew people with eyepatches in two other paintings (Figures 40 and 41).

Figure 40. Man with eyepatch.

Figure 4l. Woman with eyepatch

page 35-37.

Comparing our thoughts and feelings with the thoughts and feelings of others is a continual activity, important in regulating behavior and in maintaining emotional stability. Since language usually plays a major role in self-monitoring, the child who has difficulty understanding what is said, or making himself understood, has difficulty in monitoring himself. To the extent that art experience can enable a child to compare himself with others, and find himself adequate, it can help him control his behavior and maintain emotional balance.

John, a deaf child, age nine, was described by his teacher as average in intelligence, below average in self-esteem, and very poor in social attitudes, with much difficulty in relating to children and adults. In the art class he did not join in social exchanges. He was usually preoccupied with drawing, and with eating candy bars, which he did not offer to share.

He worked on his drawing of a farm (Figure 42) for ninety minutes. When he had finished, he rapped on the table for attention, and held his drawing up for all to see. He pointed to the cat about to land on the dog and acted out the impending fight. This behavior suggests that he used his drawing to elicit the approval of his classmates, and to assure himself that he deserved their admiration and respect.

page 38-39.

Painting is sometimes thought of as withdrawing into a private world, but it can also be an act of involvement, engaging the painter in at least three kinds of relationships. First, he relates himself to the viewer. Child or adult, he usually paints with the expectation that his painting will be seen and understood.

Second, the painter relates pictorial elements-colors, forms, and subjects, if any. He does not need green paint, for example, in order to represent grass. He can suggest grass with yellow or blue, depending on neighboring colors. He can even use black and white. If he is very young, he makes his more important subjects larger regardless of their actual size. Even if he is not young, but can allow his feelings to predominate, he may also relate pictorial elements symbolically.

Third, the painter relates to his subjects by identifying with them. In ancient China the painter was taught to lose himself in what he portrayed, to imagine himself to be a pine branch, for example, in order to capture the essential quality of pines. Similarly, the African sculptor and the contemporary expressionist try to go beyond physical appearance to essence. Their works of art not only represent ideas, they are the ideas.

In the visual arts, subjectivity is highly esteemed. The works of Picasso or Rouault can be identified at a glance, but the works of a distinguished scientist can rarely be identified by his expressive style. It is the nature of art experience to invite subjectivity, as it is the nature of science to be objective at all costs.

Children identify with their subjects spontaneously (if they are free to choose their subjects themselves). In one of the classes a little girl often drew flying birds. Each time, just before drawing them, she made little flying gestures with her shoulders, elbows, and wrists. The ten year-old who drew Figure 43 used gestures and two words to convey a message-she was in the swimming pool and her grandmother was in the coffin.

The drawing of the burglar robbing the safe (Figure 44) was made by a sixteen-year-old whose only relative, his grandmother, was terminally ill. Like the safe, his own safety seems threatened.

Figure 44. Robbing the safe

page 39-42.

EXPERIENCING CONTROL OVER

PEOPLE AND

EVENTS

The child who is inarticulate has difficulty persuading others or even letting his wishes be known, but as a painter he can be powerful. He can punish villains and reward heroes, change painful experiences into pleasant ones, and alter the appearance of objects at will.

The painting of the spook (Figure 45), by ten-year-old Lisa, seems to be an attempt at control by altering an actual experience-riding through a tunnel in an amusement park and suddenly arriving at a frightening tableau. The small figure at the bottom is herself, saying, "Help me." In putting her spook behind bars, she changed a frightening situation into a safe one.

Figure 45. Putting the spook behind bars

The drawing titled "A girl or boy in the spring?" (Figure 46) was made by a thirteen-year-old with language and hearing impairments. I overheard her classroom teacher asking her if she had ever seen a tree trunk that color, and, if not, why on earth had she used an orange crayon. In coloring the tree trunk orange she was imposing her will on the world, and with the boy saying, "Jean where Jean / very sad," was perhaps improving on reality with a little romance.

Figure 46. "A girl or boy in the spring?"

(Picture found in, Silver, R. A. (1989). Developing cognitive and creative skills through art. New York: Ablin Press.)

page 42-43.

The physiological basis for transfer lies in the adaptability of our nervous systems. A variety of stimuli can provoke us to make a particular response, and we can achieve a particular goal through a variety of means, as ethologist S. A. Barnett has pointed out. We can identify a melody regardless of the key in which it is played or the musical instrument that produces it. We recognize certain patterns as "the same" -auditory or visual or tactile- because they have relationships in common. We also generalize in response. A man who has learned to write with one hand can learn to write with the other, or even with his foot. This tolerance of variation in recognizing stimuli and responding to them develops with experience, and one of the most remarkable facts about it is that learning to do one task improves our skills at other, similar tasks (Barnett, pp. 11-12). We are also apt to generalize the effects of an unpleasant experience, or a pleasant one, to all the surrounding circumstances (Barnett, 1967, p. 176).

Can the gratifications in art experience, and the energy generated, carry over to other school situations? Eugene's behavior seems to show a transfer of attitudes that developed in the art class and subsequently became evident in his home classroom. He was a ten-year-old whose diagnosis was obscured by multiple emotional problems. He was thought to be deaf, but might have been language- or learning-impaired. Although his IQ score on the Otis scale was 89, a psychological report found average or above average intelligence, with high potential. It described him as pugnacious, inclined to withdraw when thwarted, and unable to work persistently. His teacher said he had little concept of right or wrong. The day before the art program began, his classmates went to the zoo, but Eugene had to remain in school because his behavior was so unpredictable. He lived with his mother and three siblings, his father having disappeared.

Figure 47. Eugene's family portrait

(Picture found in, Silver, R. A. (1989). Developing cognitive and creative skills through art. New York: Ablin Press.)

In our first meeting I asked him to show me who lived in his house with him, but I was unable to make him understand my request. I made a quick sketch of my own family, pointing out myself. He produced Figure 47. Where his father might be expected to stand beside his mother, there is, instead, a picture on the wall.

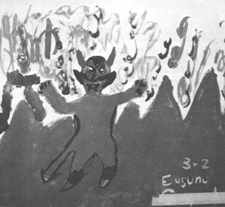

In our third meeting he painted the devil (Figure 48). Our room happened to have a glass-paneled door and was directly across the hall from Eugene's classroom. Furthermore, our meetings ended just as lunch time began. His classmates formed a line in the hall outside, admired his devil extravagantly, and escorted him away to lunch in triumph.

Figure 48, Eugene's devil

In our fourth meeting he painted the butterfly (Figure 49). When his teacher saw it, she mentioned that he had found a small dead moth in the classroom just before the art period began, and had been excited by the discovery.

Figure 49. Eugene's butterfly

In our fifth meeting he painted the group of horses galloping in a paddock (Figure 50), led by Black Beauty. (Eugene is black.)

Figure 50. Eugene's Black Beauty as leader

In our seventh meeting a classmate, arm around Eugene, asked if he might accompany Eugene to the art class, and his teacher gave her consent. His painting was an abject imitation of Eugene's painting, step by step.

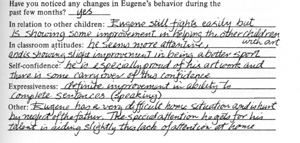

With our eighth meeting the art program ended, and Eugene's teacher completed the following questionnaire:

These modest changes in behavior suggest that Eugene's accomplishments in art had given him new status among his peers, and that he had monitored himself through his paintings. At any rate, he was put in charge of class lines, responsible for keeping his classmates in orderly rows. Since reward in learning is said to stimulate the expenditure of energy in further learning, it may be that Eugene's experiences in art helped motivate him to seek attention through approval rather than disapproval. It may also be that an improvement in self-image, developed through art, had transferred to other school situations.

This experience with Eugene impressed me with the need for objective instruments for assessing changes in behavior that might result from art experience. Even though drawings and paintings are essentially subjective, they have elements that can be quantified.

page 43-48.