Back to How Tests

Evolved

Back to How Tests

EvolvedHow Drawing Tests Evolved

Copyright 1998 by Rawley Silver, reprinted with permission

from its original publication.

No portion of this work may be copied without written consent by Rawley Silver.

The following are excerpts from

Silver, R. A. (1998). Updating the Silver Drawing Test and Draw A Story manuals; New studies and summaries of previous research. FL: Ablin Press.

Updating the Silver

Drawing Test and Draw A Story

Manuals

The purpose of this update is to bring together and summarize the journal articles and research studies performed after the Silver Drawing Test and Draw A Story were last published. In addition, their findings of reliability and validity, outcome studies, and studies of distinct populations will be summarized.

page 5.

The Silver Drawing Test

of Cognition and Emotion

(SDT)

The SDT assesses the cognitive and emotional content of responses to drawing tasks. It includes three drawing tasks: Drawing from Imagination to assess attitudes toward self and others, as well as ability to select, combine, and represent; Drawing from Observation to assess concepts of space; and Predictive Drawing to assess concepts of horizontality, verticality, and sequential order.

Responses are scored on 5-point rating scales. The cognitive scales range from low (1 point) to high (5 points) levels of cognitive skill. The emotional content scales assess responses to the Drawing from Imagination task which asks respondents to select two subjects from an array of 15 stimulus drawings, imagine something happening between the subjects they choose, show what is happening in drawings of their own, then add titles or stories. They are encouraged to change the stimulus drawings and add their own ideas. The emotional content scales range from strongly negative themes or fantasies, such as drawings about sad or helpless subjects (1 point), to strongly positive themes, such as drawings about loving relationships (5 points). The intermediate 3-point score is used for ambivalent, ambiguous, or unclear themes, and the intervening scores of 2 and 4 points, for moderately negative and moderately positive themes.

The SDT is based on the premise that cognitive skills can be evident in visual as well as verbal conventions, and that these skills, traditionally identified, assessed, and developed through words, can also be identified, assessed, and developed through drawings. It evolved from a belief that the intelligence of children and adults who have poor verbal skills is often underestimated.

Recently, the SDT was criticized for not explaining how its "drawing items" were selected. Somehow, I had neglected to include my own early studies in the manual's background literature.

page 5.

The tasks were first used with children who had severe receptive or expressive language disorders; some had both, and many had hearing loss and emotional problems as well (Silver, 1973). It was generally assumed that improving their verbal skills would improve their thinking. It seemed to me, however, that drawing could be used to develop the three concepts cited by Jean Piaget (1970) to be fundamental in logical and mathematical thinking: concepts of space, sequential order, and class inclusion.

The concept of a class requires the ability to make selections, associate them with past experiences, and combine them into a context. This concept seemed particularly important for my students because linguists had defined language as the ability to select words and combine them into sentences (Jakobson, 1964). In an attempt to bypass their language disabilities, I asked the students to select images and combine them into the nonverbal context of drawings.

To develop spatial concepts, the students drew toys and other objects from different points of view, and painted sequences of tints or shades, such as adding more and more white or red to blue. They also modeled clay to create sequences, and manipulated objects to test out their predictions.

Then I applied for a State Urban Education Project grant. Approval arrived late, after the 1972 school year started in September. Since pretests were scheduled for October, the project Evaluator had not yet been assigned, and no one else was available, I was obliged to improvise a 30-item criterion referenced pre-test. It included drawing from imagination, drawing from observation and predictive drawing, which were approved for the Project's post-tests (Silver, 1973). Later on, the drawing tasks and developmental techniques were adapted for use with stroke patients (Silver, 1975a), students with learning disabilities (Silver, 1975b and 1975c), and unimpaired students.

The SDT was first published by Special Child Publications in 1983. Revised editions were published by Ablin Press in 1990 and in 1996.

page 5-6.

Studies Published After 1996 Sex and Age

Differences in Attitudes Toward the Opposite Sex

This journal article examined fantasies about the opposite sex expressed by children, adolescents, and adults in responding to the Drawing from Imagination task (Silver, 1997). Although previous studies found that respondents tend to draw pictures about subjects the same gender as themselves, some chose subjects of the opposite sex, portraying them negatively (Silver, 1992, 1993b). The present study examined attitudes toward opposite-sex subjects found in a sample of 480 children, adolescents, and adults. Opposite-sex drawings were grouped by age and gender, scored on a rating scale adapted from the SDT Self-image and Emotional Content scales, and analyzed.

Several age and gender trends emerged. Approximately one in four (116) of the 480 respondents drew pictures about opposite-sex subjects, the proportions increasing with age. More men than women drew pictures about subjects of the opposite sex where as the reverse was found among children and adolescents, both girls and boys. The analysis of variance found males significantly more negative than females (the male mean score was 2.35; the female mean score, 2.94 (F (1, 112) = 6.92, p < .01). An age difference of borderline significance also emerged. The children and adolescents were more negative than the adults (F (1, 112) = 2- 77, p < . 10). There was no interaction.

Both genders expressed more negative than positive feelings toward the opposite sex, peaking at the moderately negative 2-point level, portraying principal subjects as ridiculous or unfortunate. Although most associations with the opposite sex were negative, one was positive.

If it is typical to express positive attitudes toward self-images, as found in previous studies, then the reverse could be expected in attitudes toward others. Although males expressed significantly more negative feelings than females, it is not necessarily evidence of misogyny, but is consistent with previous findings that more males than females drew pictures about assaultive relationships. It was suggested that drawings about the opposite sex may provide access to troubling relationships, conflicts, and opportunities for clinical discussion and intervention.

page 6-7.

Gender

Differences and Similarities in Spatial

Abilities of Adolescents

It seems to be generally agreed that males excel in spatial ability (McGee, 1979), and according to Moir and Jessel (1992), male superiority is not only confirmed but not even in dispute. Nevertheless, this study (Silver, 1996b) asked if gender differences in spatial ability are found in responses to the SDT Predictive Drawing and Drawing from Observation tasks. Subjects included 33 girls and 33 boys, ages 12 to 15, attending public schools in Nebraska, Pennsylvania, and New York. Their mean scores were analyzed using a computation of T-test scores. No significant gender differences in spatial ability were found. In Drawing from Observation, the mean scores of girls were stronger in ability to represent depth, but the probability was less than 0. 10.

Possible explanations were offered for the finding of no significant gender difference in spatial ability. Investigators who found gender differences tended to present manipulative tasks rather than drawing tasks, and it was suggested that additional samples of adult respondents might clarify the contradictory findings.

page 7.

This study asked whether different procedures (scoring success and failure vs scoring the level of cognitive skills) can explain why some studies found males superior in spatial ability while others found no gender differences (Silver, 1998). Some responses to the Predictive Drawing horizontality and verticality tasks, scored previously on the 5-point cognitive level scale were rescored in terms of success or failure. Only those respondents who drew horizontal lines in the tilted bottle (5 points) or vertical houses on the hill (5 points), were deemed successful.

Participants included 88 male and 88 female adolescents and adults. The adolescents had participated in the previous study. The adults included 26 men and 26 women, ages 18-50 (mean age 26) who had participated in studies reported in the 1996 SDT manual, a class of college freshmen in Nebraska, a college audience in New York, and residents of a detention facility in Missouri.

No significant gender differences were found either in success-failure scores or cognitive level scores. Chi-square analysis indicated that both males and females had lower scores in verticality than horizontality, more males than females. The findings supported the previous study, and suggested that perhaps some investigators had assessed knowledge of physics rather than Piagetian concepts of space.

page 7-8.

Unpublished Studies Brazilian Standardization of

the SDT

Allessandrini, Duarte, Dupas, & Bianco (1996) standardized the SDT on approximately 2,000 Brazilian children and adults, as reported in a Pre-conference Course at the 1996 Conference of the American Art Therapy Association. The children, ages 5 to 17, included subgroups based on grade, sex, and school: public and private, elementary and secondary schools. The adults, ages 18 to 40, were grouped on the basis of educational background. Group I ranged between illiteracy and the 6th grade, Group II had attended high schools. Group III had attended colleges. Each subgroup included at least 35 subjects.

An analysis of variance yielded differences in school grade and type of school, both at the .001 level of significance. The trend of growth in mean scores was similar in both cultures, increasing gradually with age and grade level. Private school students had higher scores than public school students.

Adults whose education had been limited to elementary or high schools had lower mean scores than most children, as well as the adults who attended college. They matched 7 to 8 year-old children in mean score performances. High school graduates matched adolescents ages 12-14. College graduates were superior to high school seniors.

Interscorer and test-retest reliability were also examined. Three judges, working independently, scored responses by 32 children in all school grades. The correlation coefficients were 0.94, 0.95, and 0.95 in total SDT scores, indicating strong interscorer reliability. In retest reliability, the correlation coefficients were 0.84, 0.62, 0.69, and 0.87, suggesting temporal stability.

page 8.

Comparing the SDT with

Four Diagnostic

Instruments

In a series of case studies, Horovitz-Darby (1996) compared test performances on the SDT with performances on the Kinetic House Tree Person (Burns, 1987), Kinetic Family Drawing (Burns & Kaufman, 1972), House Tree Person (Buck, 1950), and Cognitive Art Therapy Assessment, (Horovitz- Darby, 1994). Results indicated that levels of cognitive development were the same, regardless of the test instrument used.

page 8-9.

Age and sex difference in

fantasies about food and

eating

Although only two of the 15 SDT stimulus drawings are related to food or eating (the soda and the refrigerator), there seemed to be a tendency among adolescent girls to choose these subjects. Since eating disorders are becoming more common in the United States and elsewhere, the study asked whether fantasies about food appear more often in responses by adolescent girls than other age and gender groups, possibly reflecting masked anorexia nervosa, bulimia, or binge-eating.

Responses to the Drawing from Imagination task by 293 children, adolescents, and adults in previous studies were reexamined. The children, ages 9 to 10, attended fourth-grade in one private and two public schools in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and New York. The younger adolescents, ages 12 to 15, attended grades 7 to 10 in five public schools in Nebraska, New York, and Pennsylvania. The older adolescents, ages 16 to 18, were high school seniors in two public high schools in New York. The adults, ages 19 to 70, included a class of college students in Nebraska, adults in college audiences in Idaho, New York and Wisconsin, and older adults living independently in their communities in Florida. The SDT had been administered and scored by teachers and art therapists, including the author.

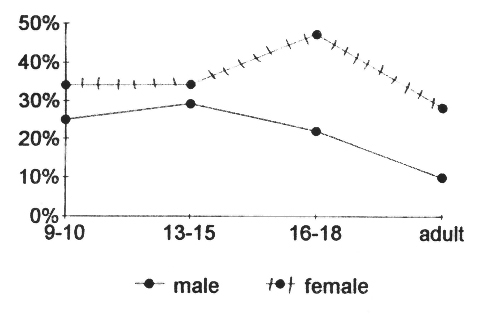

Of the 293 respondents, 85 (29%) drew fantasies about food or eating. (20 children, 40 adolescents, and 25 adults); 59 were female, 26 were male. Proportionally more females than males drew fantasies about food in each of the four age groups, as shown in Figure 1.

Among females, the largest proportion of drawings about food was found among older adolescents ages 16 to 18: 15 of the 32 girls in this sample (46.9%). The next largest proportion, 34.4%, was found among both groups of younger girls, 11 of the 32 girls ages 9 to 10, as well as 11 of the 32 ages 13 to 15. Of the 79 women, 22 (27.9%) drew fantasies about food and eating.

The group of older adolescent girls seemed more preoccupied with food than all other age and gender groups. Among males, the largest proportion was found in the sample of younger adolescents ages 13-15, (29.4%), followed by boys ages 9-10 (25%); then by adolescents ages 16-18, (22.2%); and finally, by men (10%).

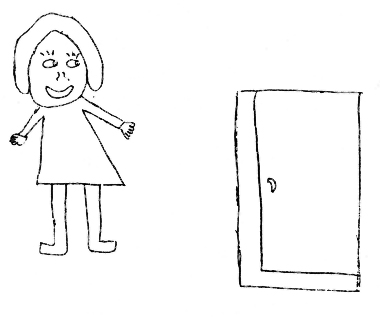

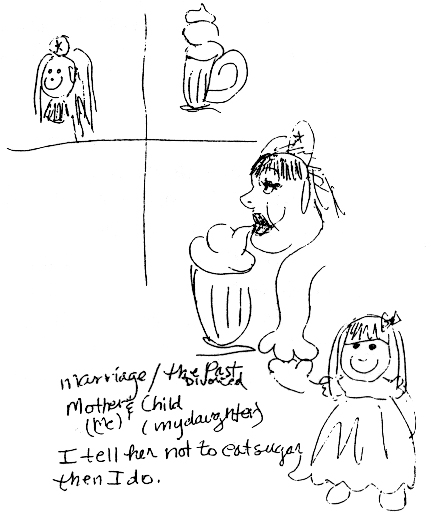

The most notable gender difference was in the proportion of responses that were ambivalent, ambiguous, or unclear (3 points): 45% of the women and girls, compared with 23% of the men and boys scored 3 points. Examples are shown in Figure 2, "The Sneaky Snacker," by a girl age 9, and Figure 3, "I tell her not to eat sugar / then I do," by a young woman.

Figure 1. Age and Sex differences in Fantasies about Food and Eating.

Figure 2. The Sneaky Snacker by a nine-year old girl.

Figure 3. "I tell her not to eat sugar / then I do," by young woman.

These findings suggest that responses to the Drawing from Imagination task about food or eating may serve to uncover masked eating disorders, and that further investigation may be worthwhile.

page 9-11.

Blasdel (1997) explored and assessed the impact of creative art experiences on the critical thinking skills of inner city students in the fifth grade. She hypothesized that experiential learning through the manipulation of art materials builds higher-order thinking, allowing the synthesis of knowledge and engagement in critical thinking skills. Critical thinking is defined as logical analysis and creative construction leading to effective problem solving skills.

The experimental and control groups were pre- and post-tested with the SDT Predictive Drawing and Drawing from Imagination subtests as well as the Cornell Critical Thinking Test (Level X). The Cornell test is a multiple choice test designed to measure what to believe, and do, in a specific situation. Although statistical significance was not achieved, extending the involvement in art experiences could yield evidence supporting the value of art experiences in building critically thinking individuals.

This study was awarded first place in the 1997 paper competition of the Kansas Psychological Foundation.

Henn (1990) examined the question whether an integrated approach to teaching can have a significant effect on the understanding of horizontal, vertical, and depth relationships by multiply handicapped students. She worked with 24 students, ages 16 to 21, using the Drawing from Observation task as a pre- post -test measure. Interscorer reliability correlations were .95 for horizontal relationships, .86 for vertical relationships, and .84 for relationships in depth. A correlation of .92 was found for combined gains on the three variables. Post-test scores were significantly higher than pre-test scores (t -2.96, p = <.0058).

Hiscox (1990) hypothesized that learning disabled students would fall within the normal range on IQ tests that were not based on language. She administered the California Achievement Test (CAT) and the SDT to 14 learning disabled, 14 reading-disabled, and 14 unimpaired children in the third, fourth, and fifth grades. Results supported the hypothesis. On both tests, the unimpaired children had the highest mean scores. The learning disabled group had higher mean scores than the reading-disabled who performed within the middle range of both groups. The difference in the mean and standard deviation between groups validated the rejection of the null hypothesis at the.05 level of significance.

Hunter (1992) compared scores of 65 college men and 128 college women, ages 15 to 53, in Australia, using five measures, including the SDT. Women appeared to perform better in Drawing from Imagination and Drawing from Observation. The contrast of gender using the multivariate set of DVs was significant (F(1,150)=5.8, p < .001). The associated univariate F test for Drawing from Imagination was significant (F(1, 150)= 13.3, p < .001, Eta2=.08), as was Drawing from Observation (F (1, 150)= 7.7, p < .006, Eta2=.05). She observed that the findings are consistent with the SDT theory that cognitive skills evident in verbal conventions can be evident also in visual conventions, and that gender differences should be considered in developing course methodology in order to facilitate learning.

Marshall (1988) worked with 9 learning disabled children using the SDT and a second measure to determine whether abilities improved. The mean total scores of the younger children in Group A increased from 16.46 to 21.09, gaining in each of the subtests. The most marked and consistent gain was in Drawing from Imagination. The adolescents in group B showed little gain, total mean scores increasing from 25.50 to 26.0.

page 11-12.

Summaries of Previous Research

It has been erroneously stated that research information on the SDT is not available, and that it is not known whether teachers or mental health professionals need training in order to administer and score the SDT

In response to these assertions, summaries of the reliability and validity studies, and other findings, are presented below. For detailed information, the reader is referred to the original publications listed in References, or the 1988, 1990, and/or 1996 manuals. The last manual received the 1996 Research Award from the American Art Therapy Association, the fourth such award for studies using the SDT.

page 12.